For most Christians, it’s obvious that the Bible needs translating. The Bible contains God’s revelation of himself to the world. It was written in languages that, today, very few people can read fluently. So making Scripture available to everyone in a language they can understand is surely a no-brainer. This conviction is one reason why the Bible is by far the most translated book in history.

However, this perspective is somewhat different to that of other religions, notably Islam. For Moslems, Allah spoke to his prophet in Arabic. The Koran is only truly the Koran in that Arabic, letter-for-letter. God is worshipped in Arabic, and anyone who is serious about Islam would do well to learn Arabic.

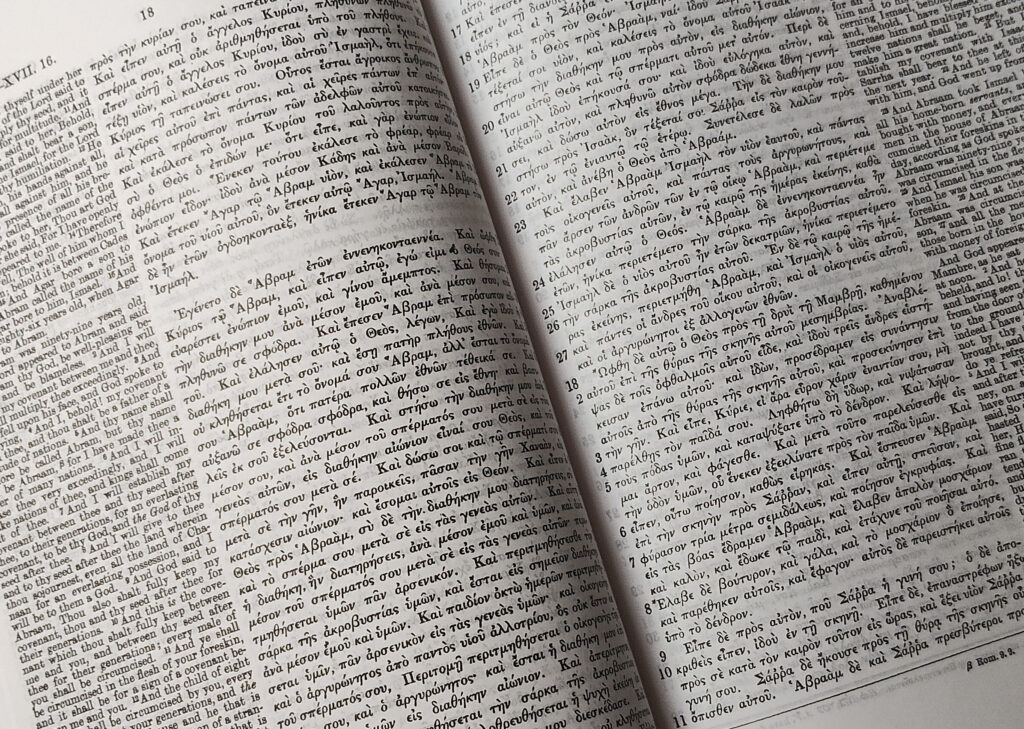

The “Christian” Scripture translation actually begins before the birth of Christ. The Jewish Scriptures (the Tanakh) were translated into Greek from the third century BCE. That translation is now known as the Septuagint. Judaism’s traditionally high view of Scripture did not prevent translation into Greek, the language of invading armies who worshipped pagan gods.

At the start of the Torah (or for Christians, Genesis 11), at Babel, God sows confusion among the world’s people through multiple languages that prevent communication. Many Christians see Pentecost (Acts 2) as a reversal of the curse of Babel. However, the result of Pentecost is not that everyone speaks the same language. The observers do not say “Wow, suddenly we are fluent in Aramean or Greek!” The miracle of Pentecost is that everyone hears God in their own language.

For Christians, Jesus is Emmanuel — God with us. God meets us in our cultures, “where we are”. Churches around the globe gather to remember Jesus through a shared meal defined by first-century palestinian culinary practices, just as the theophany participate in a meal prepared by Abraham”s family (Genesis 18). First-century Christian mission was not about exporting messianic Jewish praxis, it was about living out the implications of the Gospel in whichever culture people found themselves: under the oppression of Rome, in polytheistic Athens and to the ends of the Earth.

The aim of Bible translation has always been to make God’s word accessible to all. The fourth-century latin Vulgate translation is so-called because it made Scripture available in the lingua franca of the time. The English King James Version was intended to be understood by ordinary men and women. With time, preaching in Latin became a barrier for most people, and today the English of the KJV is often hard to understand. But both these translations were intended to let people hear God in their own language. Cultures and languages evolve, which is one reason why new translations are necessary.

Reading or hearing Scripture is one important way for men and women to learn about God. But Bible translation is more than a communication technique. It’s driven by deep theological convictions. God meets me where I am. God steps into my culture. God speaks my language. When we translate Scripture, we declare that the divine author of Scripture is indeed the God of all peoples, in all their linguistic diversity.