What is a juxtalinear?

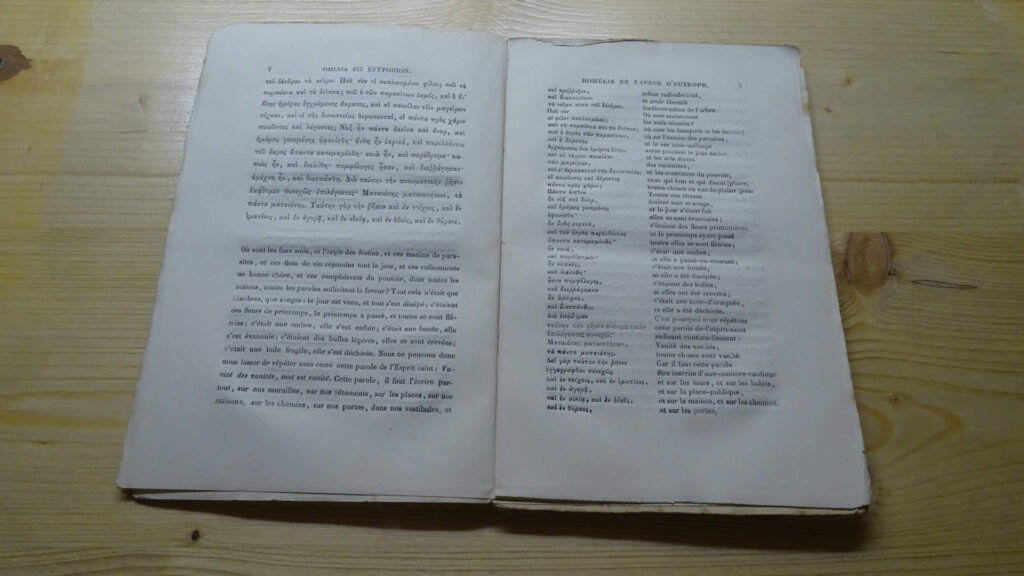

Juxtalinear translations were a 19th-20th century phenomenon in the French education

system. French grammar was taught via Latin and Greek texts. The publisher Hachette

produced around 500 booklets to help school pupils engage with those texts. They contained

the source language text and a fluid translation, but also a bilingual view. On the left, the

source language was rearranged to approach natural French word order, and broken up into

small, grammatically-meaningful chunks. On the right, there was a hyper-literal gloss, in

French, of each chunk. Publication stopped in the early 20th century and, today, few people

know about them, even among francophone linguists and classicists. (Andy Warren-Rothlin is

one impressive exception to this rule.)

What’s special about a juxtalinear?

Juxtalinears provide a bridge between source and target languages, in a way that is easy to

explain to non-linguists, that limits the risks of misinterpretation, and which leaves open most

contended options in interpretation.

Compared to a literal translation (NASB, Darby…) a juxtalinear is much closer to the source

language. This is possible because the juxtalinear gloss is not intended to be read devotionally

or from the pulpit. The gloss does not need to be elegant, it just needs to convey the sense of

the words in each chunk. For example, Greek participles, which may be translated as verbs,

nouns, adjectives or adverbs in a literal translation are systematically translated as participles

in French and English. The translator using a juxtalinear may then decide how best to render

each participle in their language.

Compared to an interlinear, a juxtalinear provides more grammatical context. Interlinears can

be convenient tools for those with some grasp of source language grammar but, in the hands of

someone with no understanding of Greek or Hebrew, they can encourage mix ‘n’ match

misassembly of words to produce incorrect meanings. A juxtalinear regroups words that belong

together grammatically, and the glosses are for those chunks rather than for individual words.

Compared to a syntax tree, a juxtalinear is more accessible and makes less interpretive calls.

Syntax trees contain a huge amount of information, but it is hard to present that information

to end users without overwhelming them. Also, a syntax tree, by its very nature, resolves every

pronoun reference and other grammatical ambiguity in the source text. Juxtalinears were

designed to be comprehensible by school children, and there are very few contended choices to

be made at the “chunk” level of a juxtalinear.

How do we make juxtalinears?

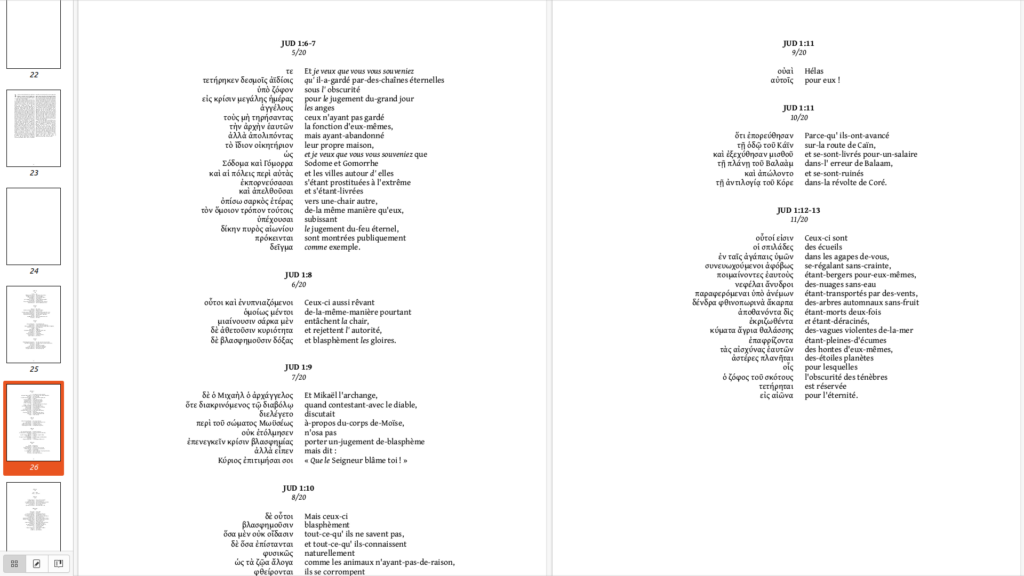

Xenizo has been working on juxtalinears for 18 months, and has gradually developed software

to support this. We currently have an online editor and a juxtalinear mode in the Scribe editor.

We start with an open-access Greek text such as the unfoldingWord Greek New Testament

(UGNT). The software generates a sentence-by-sentence view of this, after which the user may

reorder and chunk the sentence as well as adding a gloss. Today we have human-generated

juxtalinears for just over a quarter of the NT (by Greek word) and have begun experimenting

with Hebrew.

We have also experimented with machine translation of those juxtalinears. The technology

produces English juxtalinears from Greek-French sources equivalent to human final drafts. We

are awaiting feedback on machine translation to Farsi. The evidence so far suggests that we

could produce juxtalinears for many Western languages, at least, for little more effort in total

than that required to produce a reference translation in French.